Commensurability

What is commensurability?

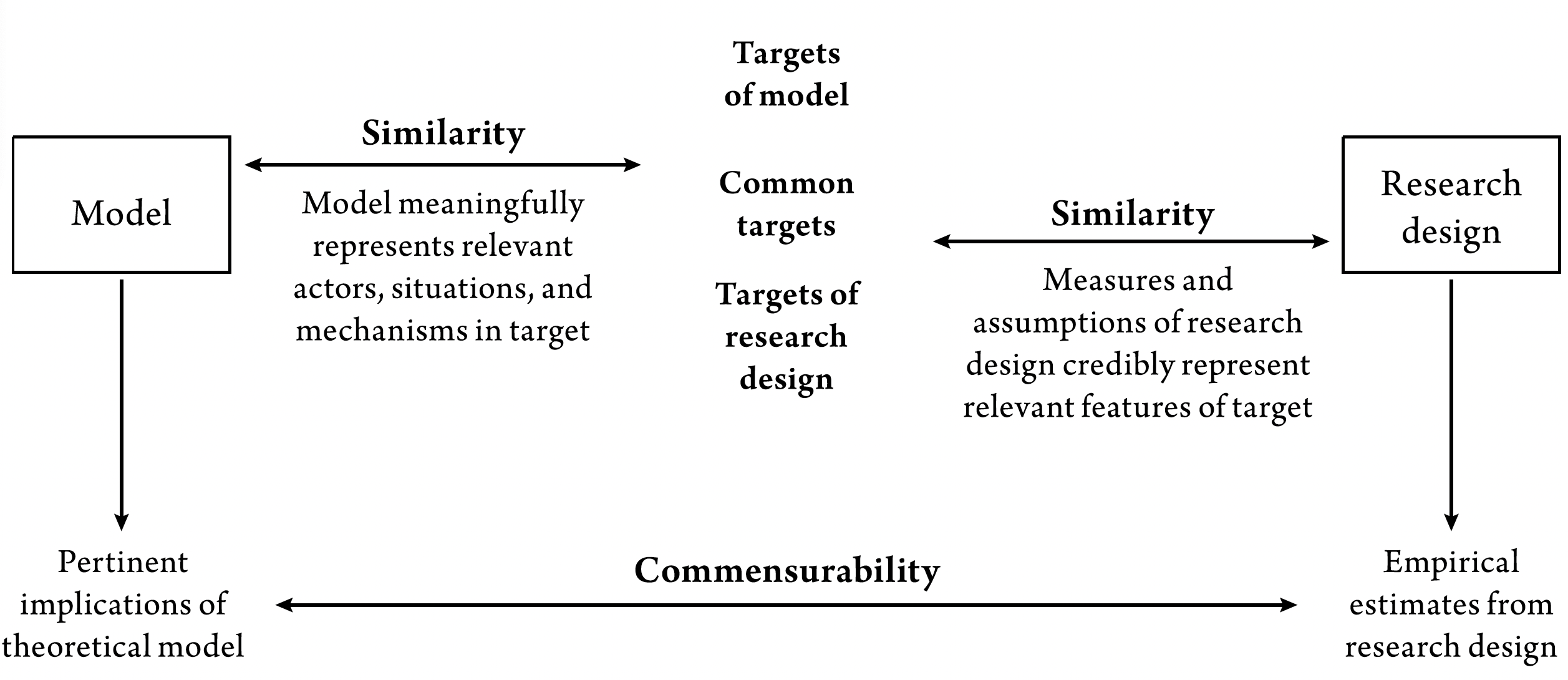

Note: Taken from “Theory and Credibility”, Figure 2.1.

Note: Taken from “Theory and Credibility”, Figure 2.1.

In “Theory and Credibility”, a research design is commensurable if the theory (formal model) and the empirical analysis are similar. That is, one should be a close as possible representation of the other. This has important implications for research design:

Theoretically-informed causal inference matters: Both models and causally identified regressions imply in essence “all-else-equal” comparisons. That is, the comparative statics are reflected in the marginal effect of the treatment, and vice-versa. Models explicitly state what variables are endogenous and exogenous, and provide clear implications on the basis of equilibrium strategies and the comparative statics. Thus models provide clear testable hypotheses, reducing the latitude for HARKing.

Measurement matters: The variables used in the empirical analysis must be good representations of the theory. Further, data constraints can limit the scope conditions of the theory. Empirically speaking, commensurability provides us with a clear understanding of bias due to self-selection and measurement error, and allow us to define the scope conditions of our findings with precision. The trade-offs between internal and external validity owing to measurement also become clearer.

Heterogeneity matters: Models often point at differences in behavior conditional on the values of the parameters. This can be revealed for instance by cut-off strategies and/or an analysis of the comparative statics (cross-partials and second or higher order partial derivatives). Empirical analysis can (and should) test for the related implications by means of an analysis of the heterogeneity of the treatment effects. This relaxes the assumption of constant treatment effects, and it emphasizes the need for using heterogeneity-robust estimators which have become standard.

Moderators and mediators are useful for assessing mechanisms: Models are explicit about the behavior of their endogenous variables. In this sense, they can can guide the research design to select and analyze moderators (i.e., interaction effects) and mediators (i.e., intermediate outcomes) to rigorously test theories. In this regard, relaxing assumptions in the model - endogeneizing - can reveal new and interesting mechanisms and additional testable hypotheses; i.e., models serve for the purpose of exercising logical consistency in the research design to uncover new perspectives.

Abduction strengthens the research design: When empirics do not confirm the model, the empirics can be revised to check if it is properly testing the model (e.g., are measures commensurable? is the econometric specification commensurable?); the model can also be revised by relaxing/imposing assumptions if its predictions are not confirmed. This leads to a fruitful back and forth between theory and empirical analysis that strengthens research design and reveals new, and interesting results. In other words, theory guides empirics, and empirics helps revising theory.